The moment I arrived in Japan, the sense of order was palpable. I spent two days in Tokyo, where everything flowed smoothly and ran on time despite the chaotic buzz of the city. You could sense there was great pride in discipline: people waited in line, trains arrived on the dot, and cleaning crews kept the city spotless. And, despite the fact that my Japanese vocabulary consisted only of “kon’nichiwa,” it was easy to get from the plane to my hotel with the help of warm welcomes and constant bows.

I used the jet lag to my advantage and visited Tokyo’s famous fish market before dawn. Weathered-looking fish mongers prepared the catch of the day, totally unphased by onlookers. It’s something I noticed everywhere—an intense focus on the task at hand and a commitment to the perfection of the craft, whatever it may be. Speaking of perfection, my dinner at Sense at the Mandarin Oriental Tokyo had a magical view straight out of Lost in Translation and a crispy duck dish that was perfection on a plate.

I stayed at the Aman Tokyo. It sounds crazy, but what stuck with me was lobby’s mesmerizing ceiling. And the bacon. It’s served crispy or regular—whatever you want—just one small example of the top-notch service and sense of hospitality found countrywide. On our second day, the server remembered my name and my love of the crispy bacon. The attention to detail at this property was out of this world.

We worked our way out of the city, each stop smaller in size and population than the last. From bustling, modern Tokyo to traditional Kyoto, to Nara, an ancient capital outside of Tokyo. Nara was a contrast to Tokyo’s metropolis, with its park of free-roaming friendly deer and the structures left behind from Japan’s Imperial period. We tasted sake, ate at an izakaya surrounded by businessmen toasting “kampai,” and tasted cocktails at Lamp Bar, where owner Michito Kaneko was named the world’s best bartender in 2015. It was Japan-meets-Prohibition as he poured Japanese whiskeys and flaming concoctions into ornate glasses.

My first ryokan experience was at Koto No Yado Musashino, the oldest of these Japanese-style, minimalist inns in Nara. Staying in a ryokan is an unexpected experience, unlike Western travel. I left my shoes at reception for a pair of wooden flip-flops. I entered my room and couldn’t find a bed. I learned that futon-like mattresses are only laid out after dinner—and I learned to ask for it to be prepared much sooner, so I could fit in a nap. The tradition took some getting used to, but the private Zen garden and hot tub were well worth the trade-off.

The route from Nara to Yoshino was filled with cedar forests and so many temples that I lost count. Our roads were car-free, shaded by a canopy of moss growing on trees and accompanied by the sound a flowing stream—super Zen. In Yoshino, we ate soba noodles with the locals and the proprietor took us to meet his three-week-old puppies.

Our Yoshino ryokan was built of cedar and felt like a treehouse. My room had a bathroom, but no shower, and this is how I discovered the onsen, for better or for worse. Onsen are traditional, shared baths—in this case, an indoor/outdoor pool of heated mineral water. You’re given a simple robe called a yukata, which gets tossed aside once you climb in for a soak. It took some getting over my Western modesty, but I’ll admit it was more relaxing and soothing than a shower (especially after a day of riding).

You also wear your yukata to the kaiseki dinner at the hotel—on the upside, it takes the stress out of deciding what to wear. The owner brought out course after course of elaborate dishes herself: small plates of sashimi, persimmon salad served in a carved-persimmon bowl, and a tiered tray of small bites. It’s all presented with the quality and care reserved for America’s Michelin-starred restaurants.

Japan is completely in tune with a cyclist’s diet. Cyclists know that what we eat is directly related to how we perform, and Japanese dining culture is centered on clean food of excellent quality with local, seasonal ingredients. It wasn’t the grain bowls or salads I eat at home, but the food makes you feel good and it’s easy to embrace (even if I still missed the occasional croissant when miso soup was served every day at breakfast).

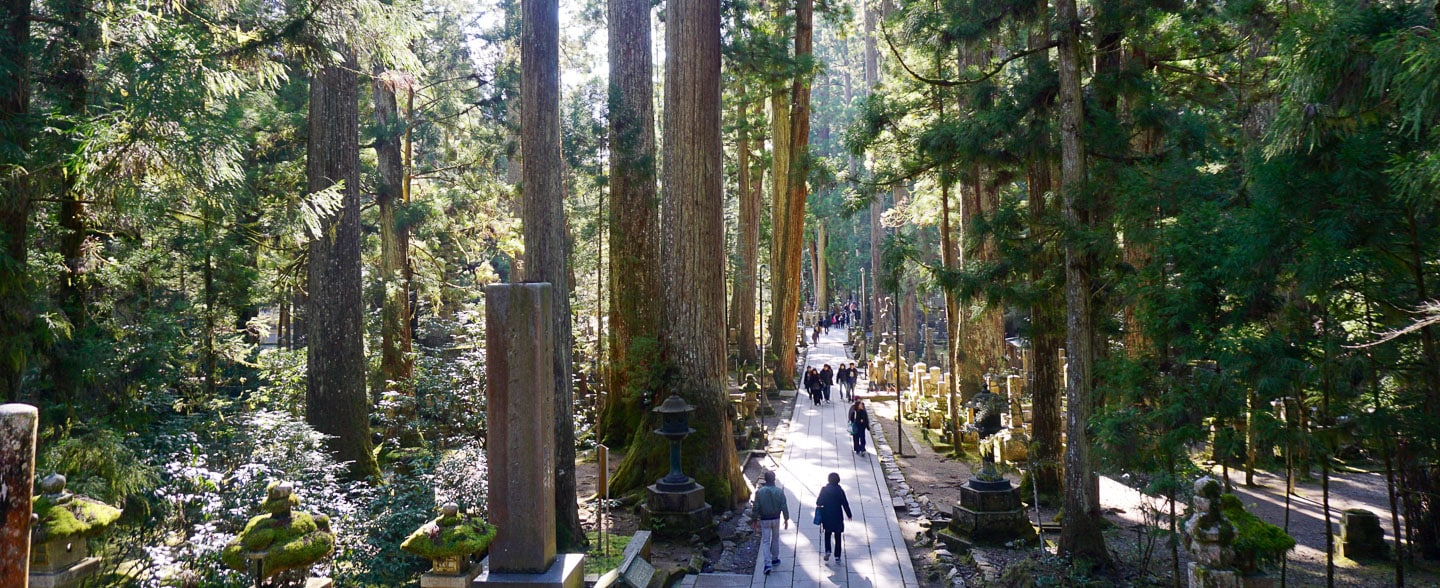

Our last day in the Japanese countryside took us to Koyasan, the center of Shingon Buddhism since 816 A.D. It’s a long climb through the woods to reach this mountaintop town. Pilgrims come from around Asia to hike to this village, but we make our pilgrimage by bike instead. The temple complex here was impressive and the Okunoin cemetery was otherworldly. As we walked the empty paths that strayed deep into the shade of cedar trees, this hardly seemed like the same country as Tokyo.

Every part of Japan is different, and Japan itself is different than anywhere I’ve ever been. Japan is Japan: it’s simple, but it’s also complex. It’s a place all about juxtaposition, and it’s best understood by bike. You only live once—take my word for it, and go to Japan.